When I first started covering aerospace, Russia was the poster child for rocket bravery – think Gagarin’s historic flight and the massive R‑7 launchers that launched satellites, spies, and crews alike. Fast forward to September 2025, and the picture looks starkly different. President Vladimir Putin walked into the Kuznetsov design bureau in Samara and, in plain terms, asked engineers to sprint on engine development while the country’s space budget is being slashed by sanctions and war‑driven costs.

The sanctions squeeze on propulsion tech

Over the past three years the United States, the EU and their allies have rolled out more than sixteen sanction packages that zero in on Russia’s defense and space sectors. The aim? To choke off the flow of high‑temperature alloys, advanced electronics and polymer composites that are essential for modern rocket engines. In January 2025 the U.S. State Department added another layer, black‑listing over 150 individuals and entities linked to the production of rocket engines – from the Central Research Institute for Special Machinery to the Joint Stock Company Research Institute of Physical Measurements.

What does that mean on the ground? Russian firms can no longer order the ultra‑light composites that keep an engine’s weight down, nor can they import the precision‑made valve assemblies that survive the thousands of degrees inside a combustion chamber. The result is a scramble for "import substitution" that often ends up using older, bulkier domestic parts that cost more and perform worse.

The fallout hit the wallet too. When Russia halted RD‑180 exports to the United States in 2022 as retaliation, it lost a lucrative revenue stream that helped fund research and development. That loss, combined with the drop in foreign technology licences, pushed RSC Energia – the crown jewel behind Soviet‑era rockets – into a financial abyss. The company now carries multi‑million‑dollar debts that have forced it to shelve a backlog of projects and lay off critical staff.

What’s at stake for Russia’s space future?

Beyond the balance sheets, the crisis threatens every big‑ticket program on the Russian calendar. The lunar lander project dubbed "Oriel" – intended to showcase a docking and landing system for a future moon base – now faces indefinite delays, scaled‑back objectives, or outright cancellation if engine supply problems aren’t solved.

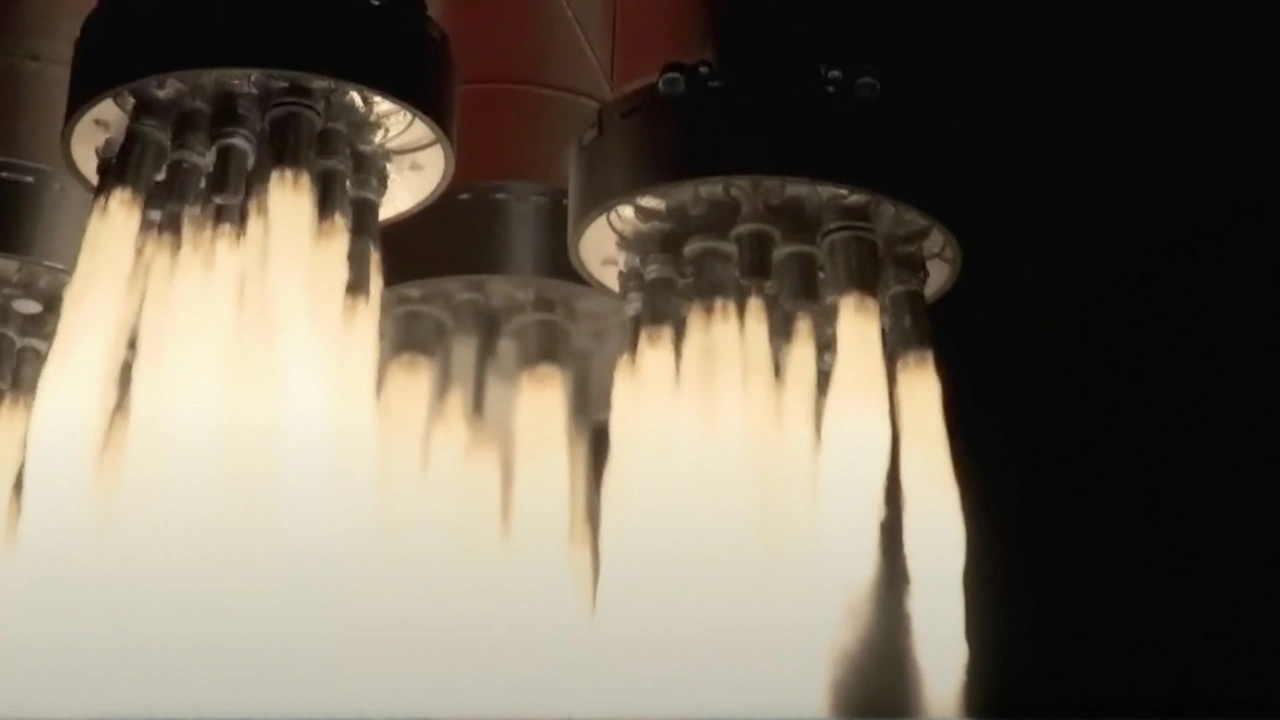

Even domestic launch capabilities are at risk. The RD‑107 and RD‑108 engines, legendary for powering the R‑7 family that lifted Yuri Gagarin, are aging and need modern upgrades that require materials now locked behind sanctions. Without a new generation of thrust‑producing machines, Russia could be forced to rely on outdated designs or, worse, hand over more launch slots to private Western providers.

Put simply, the Russia rocket engine crisis is a bottleneck that could push the nation out of the top‑five league it once dominated in aircraft and rocket engine production. The country’s historic bragging rights – from the NK‑32 turbofan that still powers the Tu‑160 Blackjack bomber to the RD‑180 that once fueled both Russian and U.S. rockets – are being eroded by a mix of geopolitical isolation and a lack of cutting‑edge parts.

Despite the grim outlook, there are a few bright spots. Over the past four years, aircraft engine deliveries rose by more than 50 %, climbing from 791 to 1,227 units, and the government announced successful import substitution for engines used in Ansat helicopters and Sukhoi Superjet aircraft. The new VK‑650V gas turbine and PD‑8 turbojet claim to meet global standards, showing that Russian engineers can still innovate when pushed.

However, those successes sit on a fragile foundation. The Kuznetsov facility, once the heart of Soviet propulsion breakthroughs, now grapples with outdated tooling, brain drain and a shrinking pool of foreign partners. Its storied past – producing the RD‑107/108 engines that launched the first human into space and the NK‑32 that still roars under a strategic bomber – underscores how far the current predicament diverges from past glory.

Looking ahead, the government’s push to accelerate engine development will hinge on three pillars: securing stable funding, rebuilding a supply chain that can produce high‑grade alloys domestically, and attracting the next generation of engineers. Some analysts suggest that a tighter partnership with friendly nations like China could fill material gaps, but political realities make such cooperation delicate.

If these hurdles aren’t cleared, Russia risks watching its launch pads stand idle while competitor nations, from the United States to emerging players like India, fill the vacuum. The long‑term implications extend beyond prestige – they affect national security, satellite communications and even the country’s ability to generate export revenue from its once‑lucrative space services.

For now, the engines at the Kuznetsov bureau hum, but the sound is tinged with urgency. Whether Russia can reignite its propulsion prowess or will settle into a diminished role remains the big question on the horizon of global space exploration.

Comments (7)

It is clear that the loss of foreign‑made high‑temperature alloys has forced Russian engineers to revert to heavier domestic materials which inevitably lowers thrust‑to‑weight ratios and hampers performance across the board while the broader aerospace community watches with a mix of concern and curiosity about how Russia will adapt to these constraints. The ongoing budget cuts compound the material shortages by limiting the ability to fund new tooling and research projects that could otherwise mitigate the impact of sanctions and keep the RD‑107 and RD‑108 families relevant in an evolving market. Nevertheless the historical resilience of the Russian space program suggests that collaborative problem‑solving within the domestic supply chain may still yield incremental improvements if the government maintains steady financial support and encourages knowledge sharing among research institutes.

What a fascinating and sobering picture emerges when you look at the current state of Russian propulsion-everything from the aging RD‑180 legacy to the new VK‑650V attempts shows both ingenuity and strain, and it really highlights how geopolitical pressures can reshape entire industries in just a few years. It’s impressive that despite these hurdles some domestic engine programs are still seeing production growth, yet the long‑term outlook remains uncertain without a clear pathway to acquire critical high‑grade materials.

According to recent data the Russian aerospace sector saw a 12 % decline in overall launch capacity between 2022 and 2024, a trend directly correlated with the reduction in imports of specialised composites and precision valve components. The financial strain on RSC Energia has also led to a slowdown in the development of the Oriel lunar lander, pushing its projected launch window further into the future.

The story of a nation's rockets is, in many ways, a mirror reflecting its resolve against external pressure.

When sanctions aim to choke the lifeblood of propulsion technology, they inadvertently test the depth of a country's ingenuity.

Russia's heritage of daring feats, from Gagarin's ascent to the formidable R‑7 family, embodies a spirit that cannot be extinguished by a single embargo.

The current scarcity of high‑temperature alloys forces designers to reconsider traditional engineering pathways.

Yet history teaches that necessity is the mother of invention, and new alloy formulations may arise from domestic research laboratories.

The financial turbulence facing entities like RSC Energia is a symptom of broader geopolitical isolation, but it also acts as a catalyst for internal restructuring.

By reallocating resources toward home‑grown composite technologies, the Russian aerospace sector can reduce its dependency on foreign supply chains.

Such a shift, however, demands sustained governmental commitment to fund advanced metallurgy programs and to protect critical talent from brain drain.

The collaboration with allied nations, particularly China, offers a pragmatic avenue to bridge material gaps while respecting strategic sovereignty.

Critics argue that reliance on external partners undermines independence, yet no nation thrives in complete isolation in today's interconnected world.

The upcoming VK‑650V turbine represents a step toward self‑sufficiency, showcasing that engineering excellence can persist even under duress.

If Russia can successfully integrate these domestically produced components into the next generation of rockets, it will reaffirm its position among the top five space powers.

Failures, on the other hand, could relegate the nation to a supporting role, supplying launch slots to commercial Western entities.

The choice, therefore, rests not solely on material availability but on the collective will to adapt, innovate, and preserve a legacy of exploration.

In the final analysis, the engine crisis is less a sign of decline and more a crucible forging the future identity of Russian space endeavors.

Wow, the struggle feels endless 😢

It's interesting to see that the new PD‑8 turbojet reportedly meets international standards, which could open doors for export opportunities if the political climate eases 🙂. Keeping an eye on how these engines perform in real‑world tests will be key to assessing whether Russia can regain some of its lost market share.

Totally agree, the optimism around those test flights is refreshing and it shows that even with setbacks the community can stay hopeful about future breakthroughs.