When National Social Security Fund (NSSF) rolled out its third‑phase rates on February 1, 2025, Kenyan employees felt the pinch immediately.

The change came as part of a five‑year rollout of the NSSF Act 2013, a law that obliges anyone over 18 covered by the Employment Act to contribute toward a retirement pot. Under the new tiered system, the lower earnings limit rose from KSh 7,000 to KSh 8,000, while the upper limit doubled from KSh 36,000 to KSh 72,000. Both employees and employers still fork out 6 % of salary up to those caps, but the math now pushes monthly deductions higher across the board.

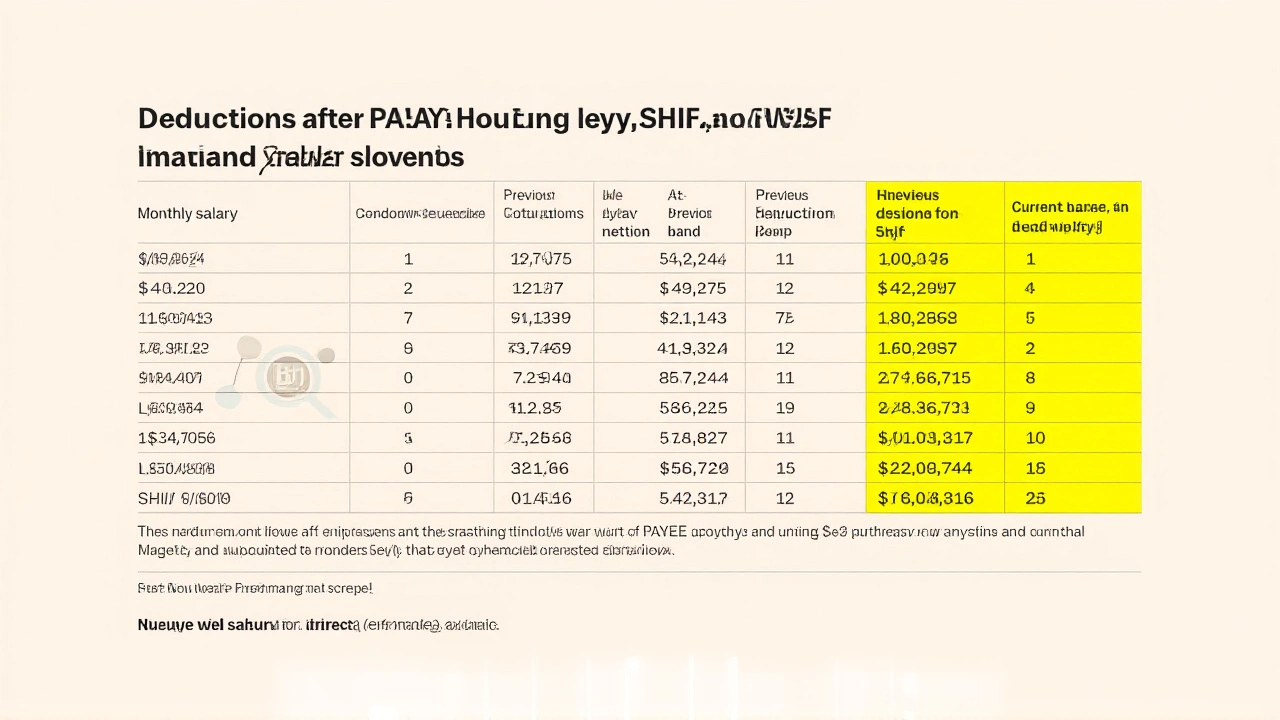

Here’s the thing: a worker pulling KSh 50,000 a month now sees a KSh 3,000 contribution rather than KSh 2,160. Someone earning the new ceiling of KSh 72,000 faces a KSh 4,320 cut – that’s a bite of up to KSh 1,512 from take‑home pay. For many families, that extra squeeze feels like a sudden rent hike.

How the New Tiered Model Works

The two‑tier architecture separates contributions. Tier I, capped at the lower earnings limit, goes straight into the NSSF’s core fund. Tier II, which applies to earnings between the lower and upper limits, can be funneled into a contracted‑out scheme of the employer’s choice. If an employee is already part of a pension plan that meets standards set by the Retirement Benefits Authority (RBA), they can opt out of Tier II only – Tier I remains mandatory.

In practice, this means that a mid‑level earner at a Nairobi‑based manufacturing firm will see both the employee‑side and employer‑side contributions rise from KSh 2,160 to KSh 3,840 each month. The total payroll outlay jumps by KSh 1,680 per staff member, a figure that HR departments are already grappling with.

Why the Government Pushed the Increase

The official line, echoed in statements from the Ministry of Labour, is simple: higher contributions will translate into larger retirement payouts and broader social‑security coverage. The Act’s Schedule 3 ties the upper earnings limit to twice the national average salary – a metric that has risen sharply over the past decade, prompting the recalibration.

Analysts note that the shift away from a flat‑rate contribution toward a progressive, earnings‑based model mirrors reforms in South Africa and Ghana, where similar moves have helped shrink pension gaps. "The short‑term pain is real," says James Mwangi, senior economist at Capital Insights, "but the long‑run benefit could be a 30 % boost in average pension benefits by 2035."

Reactions From Workers and Employers

Unions reacted with a mix of resignation and pragmatism. The Kenya Trade Union Congress (KTUC) held a press briefing on February 3, urging the government to consider a phased salary supplement for low‑income earners. "We understand the intent," said KTUC secretary‑general John Mutua, "but the reality on the ground is that many households survive on the margin. A KSh 1,500 reduction can mean the difference between paying for school fees or not."

Employers, especially in the SME sector, are scrambling to adjust payroll software and re‑budget for the added 6 % employer contribution. A Nairobi‑based tech startup disclosed that its monthly payroll processing costs rose by roughly KSh 200,000 after the change.

Potential Ripple Effects

Beyond individual wallets, the higher infusion of cash into the NSSF could strengthen its investment capacity. The Fund has been eyeing government bonds and infrastructure projects, and a larger contribution base may enable more aggressive asset allocation. This, in turn, could stimulate the Kenyan capital market, a point highlighted by the Nairobi Securities Exchange’s chief economist, Aisha Omar.

On the flip side, the increased labor cost may dampen hiring in price‑sensitive industries. Early data from the Central Bank shows a slight uptick in vacancy durations for entry‑level positions since March.

What’s Next for the NSSF Roadmap?

The final phase of the five‑year plan is slated for 2027, when the upper earnings limit will be revisited to reflect new wage data. Meanwhile, the NSSF board has pledged to roll out an online contribution calculator by the end of the year, aiming to improve transparency and help workers see exactly how their future pension will grow.

For now, the deadline to lodge the new contributions remains the 9th of each month. Payroll officers are urged to double‑check figures, especially for staff on mixed‑pay structures or those who have just transitioned into a registered pension scheme.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much will a worker earning KSh 40,000 see deducted after the new rates?

At the 6 % employee rate, the contribution rises from KSh 2,400 to KSh 2,640 per month – a KSh 240 increase. Employers also add KSh 2,640, so total payroll outlay climbs by KSh 480.

Can employees opt out of the higher Tier II contribution?

Only if they are already enrolled in a RBA‑approved pension scheme that meets the required contribution threshold. In that case, they remain liable for the mandatory Tier I portion.

What impact does the increase have on small businesses?

SMEs face a proportional rise in labor costs – roughly KSh 200,000 extra per month for a 50‑employee firm paying average salaries. Many are seeking short‑term cash‑flow support from banks to absorb the shock.

When will the NSSF publish the new contribution tables?

The Fund announced that updated tables and an online calculator will go live on its website by 31 December 2025, giving employers a year to adjust systems before any further changes.

How does this reform compare to pension changes in neighboring countries?

Like Kenya’s new tiered model, Tanzania introduced a graduated contribution scheme in 2022, and Uganda did so in 2023. All three aim to boost future payouts, though Kenya’s jump in the upper limit is the steepest in the region.

Comments (13)

Man, the new NSSF rates are a real wake‑up call for a lot of Kenyan workers. It’s crazy how a few extra keshes can tip the balance on a family’s budget. I feel for anyone pulling a mid‑range salary; that extra KSh 1,500 really hurts. At the same time, the idea of a bigger retirement pot isn’t without merit. If the fund can actually deliver better pensions down the line, maybe the short‑term pain is worth it. Employers should definitely look into ways to smooth the transition for staff, maybe by offering small allowances or staggered adjustments. And employees, keep an eye on those payslips – double‑check the calculations, especially if you have a mixed‑pay structure. It’s also a good time to talk to HR about any existing private pension plans you might have. Stay solid, Kenya, and keep pushing for transparent communication.

Well looks like the NSSF just decided to *generously* take a bite out of our wallets huh??

Quick heads‑up: the 6 % dip means a KSh 240 rise for a KSh 40k earner, so keep an eye on that line in your slip 🙂

It is evident from the recent adjustments that the NSSF’s policy shift is driven by a desire to enhance long‑term social security for Kenyan employees. While the immediate impact on take‑home pay is undeniably palpable, one must also consider the prospective augmentation of retirement benefits, which may offset the current reduction. Employers are encouraged to communicate these changes transparently to their staff and to explore supplemental measures where feasible. In sum, the reform, albeit stringent in the short run, aligns with broader fiscal objectives.

Absolutely, I think it’s important we all stay supportive of each other during this transition. Small talks with teammates can help share tips on budgeting, and maybe HR can offer some guidance on the new calculations.

Honestly, it feels like the government just tossed a tax on us without any runway 😒💸. If they really cared about retirement, they’d fund it directly instead of draining our paychecks. But hey, guess we’ll just have to survive.

The new NSSF rates are a classic case of policy makers focusing on future benefits while ignoring present realities. Workers see less money in their pockets and wonder how they will pay rent or school fees. Employers also feel the pinch because they must match the 6 % contribution on top of wages. Payroll departments are scrambling to update software and recalculate figures for every employee. The fund claims that a larger contribution pool will boost investment capacity and ultimately raise pension payouts. In theory that sounds good but in practice the immediate cash flow squeeze can lead to reduced hiring. Small businesses may even cut back on hiring or delay expansions. Some analysts compare this to similar reforms in South Africa and Ghana where the long term outcomes are still being measured. The Kenyan labor market is already showing longer vacancy durations for entry level positions. If the trend continues it could slow economic growth. On the other hand a stronger NSSF could stabilize the retirement system and reduce poverty among the elderly. The government’s justification hinges on projected 30 % increase in average pensions by 2035. That projection assumes consistent contribution growth and solid fund performance. Critics argue that the fund’s management has been opaque and that higher contributions do not guarantee better returns. Ultimately the success of this reform will depend on both fund governance and the ability of workers to absorb the short term loss.

The approach taken by the Kenyan authorities reflects a shortsighted fiscal agenda that undermines the very citizens it purports to protect. By imposing steeper deductions, the government disregards the economic realities faced by its labor force and jeopardizes domestic consumption. Such policies betray the principles of responsible stewardship that should guide any nation’s financial strategy. It is incumbent upon policymakers to prioritize sustainable growth over half‑hearted social schemes. Moreover, the rhetoric of future pension security rings hollow when today’s workers are forced to sacrifice basic necessities.

From a macro‑financial perspective, the marginal increase in payroll tax liability translates into a measurable uptick in the NSSF’s actuarial reserve, potentially enhancing its solvency ratio. However, the elasticity of labor supply in the informal sector may experience a negative shock, leading to a shift in the employment‑wage equilibrium. The net present value of incremental contributions must be weighted against the opportunity cost of reduced disposable income on aggregate demand. In short, the policy’s efficacy hinges on effective fund governance and macro‑economic spillover effects.

Honestly, this whole situation is a stark reminder that governments love to play the long‑term hero while crushing everyday people in the present!! It’s a classic sacrifice‑the‑few for the imagined‑greater‑good narrative!! If they truly cared about the welfare of Kenyan families, they would have rolled out a more equitable financing plan!! Instead we get an abrupt KSh 1,500 hit to take‑home pay!!

I concur with the concerns raised regarding the immediate financial burden on employees. It is essential that the NSSF ensures transparent communication and provides accessible tools for workers to understand the long‑term benefits. A balanced approach would mitigate short‑term hardships while preserving the intended enhancement of pension outcomes.

Meh, more tax. Not happy.

It’s interesting to see how pension reforms across Africa share common threads, yet each country adds its own cultural flavor. In Kenya this move may spark community discussions about collective responsibility and support for elders. Let’s hope the conversation stays constructive and that the funds truly reach those who need them most.